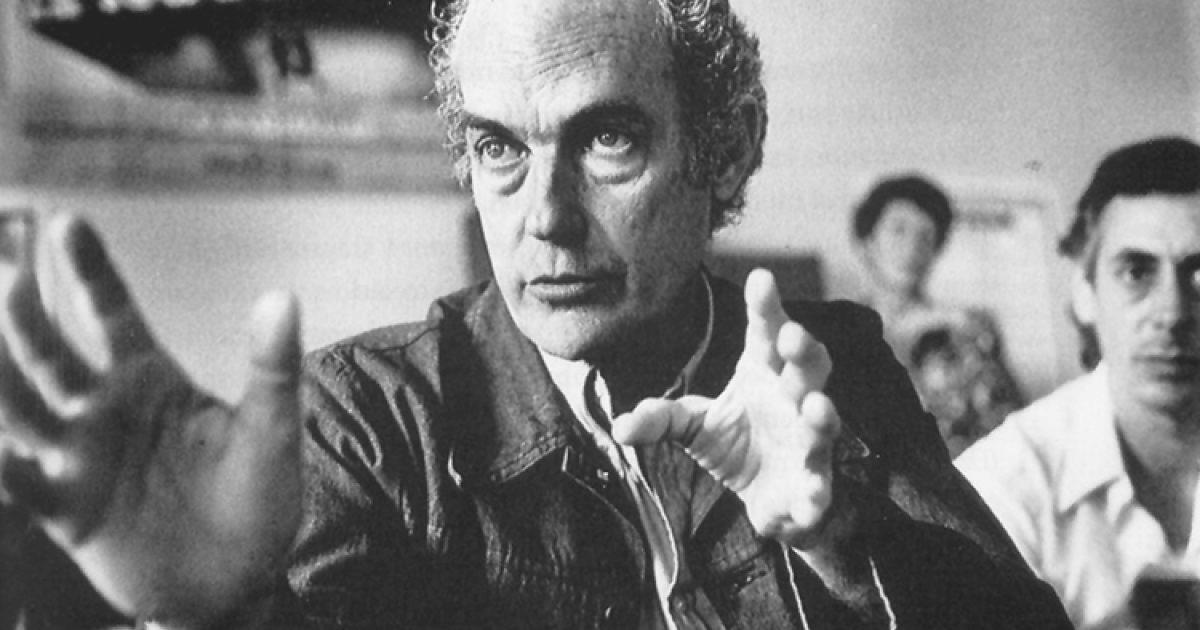

Tomás Gutiérrez "Titón" Alea (1928-1996)

When discussing auteur cinema beyond Europe and the United States, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea stands out as a defining voice in Latin American film. Known simply as Titón in Cuba, Gutiérrez Alea was not only a director with a distinct cinematic vision, but a filmmaker deeply engaged with his country’s political and cultural contradictions. His work doesn’t just reflect Cuba—it interrogates it, complicates it, and occasionally mourns it. Gutiérrez Alea left a recognizable imprint on every film he made, and his career offers a powerful example of how auteurism can operate within, and often against, the ideological pressures of a revolutionary state. I believe that the reason that we can most reflect on Titón as an auteur was for his signature nuanced storytelling of Cuba’s national issues, mixing it with the aesthetics of Italian Neorealism. When looking at vast amounts of Cuban cinema, you are able to see Titón’s influence or his touch within a matter of a scene or two.

Born in Havana in 1928, Gutiérrez Alea came from a bourgeois family, studied law at the University of Havana, and later trained in film at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in Rome. There, he was exposed to Italian Neorealism, which left a lasting influence on his aesthetic approach. After returning to Cuba, he helped found the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC) in 1959, the same year as the Cuban Revolution. His filmmaking would become inextricably linked with the hopes, contradictions, and disillusionments that followed. While deeply committed to the revolutionary project, Gutiérrez Alea was never a propagandist. Instead, his films often walk a fine line between support and critique, using irony, humor, and contradiction as tools of both loyalty and resistance. This tension is central to his identity as an auteur. His films are ideologically charged but also introspective, formally inventive yet grounded in lived Cuban experience. He found ways to question power without losing access to it, and that balancing act defines much of his work.

His breakthrough film, Memorias del subdesarrollo (1968), remains his most iconic. Following a bourgeois intellectual who chooses to remain in post-revolutionary Havana while others flee to Miami, the film mixes documentary footage, fictional narrative, and inner monologue to portray a society in flux. The protagonist is paralyzed by indecision and alienation, and through him, the film reflects Cuba’s own uneasy transformation. It is both a love letter and a lament, a film that captures the psychological cost of revolution without abandoning its ideals. Formally daring and politically complex, Memorias established Gutiérrez Alea as a director capable of turning national contradictions into cinema. This is perhaps the most well-known cuban film, with filmmakers like Martin Scorcese and Francis Ford Coppola both naming it one of the most important films of the 20th century.

His later works continued this negotiation. La última cena (1976) critiques colonial hypocrisy through a stylized historical parable. Hasta cierto punto (1983) explores machismo and the limits of ideological change in gender relations. Even Fresa y chocolate (1993), co-directed with Juan Carlos Tabío, brought his work to international audiences by addressing censorship, homosexuality, and tolerance within Cuban society. The film, warm and humanist, is also politically loaded, challenging the moral certainty of revolutionary dogma at a time when Cuba was entering the crisis of the Special Period.

What defines Gutiérrez Alea as an auteur is not only a consistent visual style in the way we might see with Kubrick or Wes Anderson. Instead, it is his intellectual framework, his belief in cinema as a space for dialogue, not dogma. A nuanced voice in a very censorship filled country. He approached film as both a citizen and an artist, using the medium to probe, reflect, and provoke. His blending of fiction and documentary, his self-reflexive narration, and his deep concern with Cuban subjectivity form a recognizable sensibility. One that is ironic, curious, and always politically alive.

His legacy today remains vital. For Cuban filmmakers navigating censorship, limited resources, and ideological pressure, Gutiérrez Alea offers a model of creative resistance. His work shows that being an auteur is not just about style or signature. It is about vision, and the courage to hold complexity in the frame without resolving it. In that way, he not only shaped Cuban cinema, but expanded the definition of what auteurism can look like on the margins of global film history.