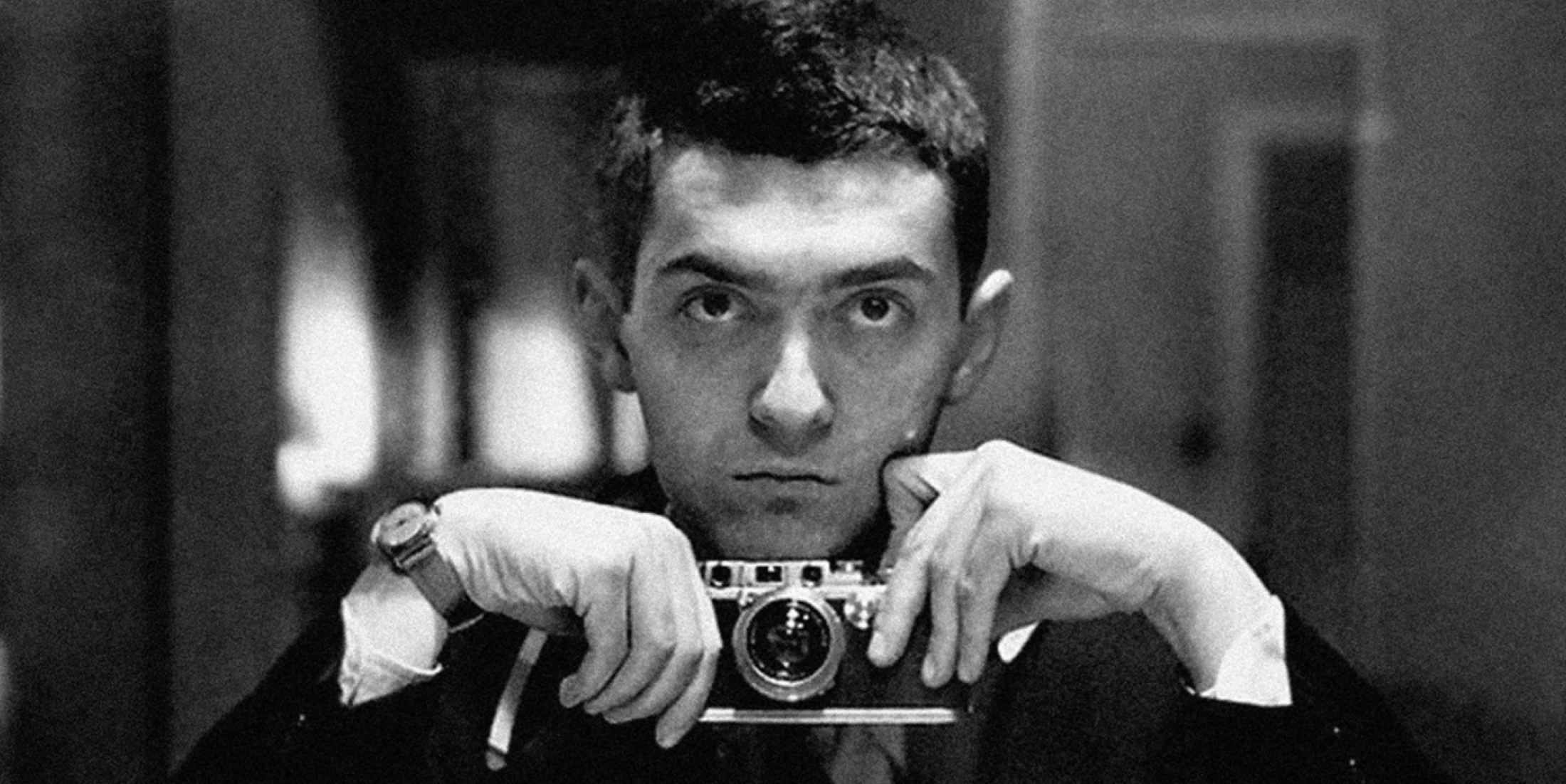

Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999)

When we talk about the concept of the auteur in cinema, few names appear more consistently than Stanley Kubrick. Across academic criticism, film studies, and popular conversations, Kubrick stands as a definitive example of what it means for a director to be the primary creative voice behind a film. His work crosses genres, generations, and national borders, but each of his films carries a distinct signature. Kubrick did not simply direct movies; he shaped them according to a singular vision that is both rigorous and deeply philosophical.

Stanley Kubrick was born in New York City on July 26, 1928, into a Jewish family of Austrian and Polish descent. Raised in the Bronx, he discovered photography as a teenager and eventually became a staff photographer for Look magazine. Though he never studied film formally, he approached the medium with obsessive discipline, teaching himself the craft through early short documentaries and low-budget features. By the early 1960s, he had relocated to England, where he would spend the rest of his life working in near-complete privacy. Kubrick died in 1999, just before the release of his final film, Eyes Wide Shut.

What separates Kubrick from other filmmakers is not just technical skill, but the total control he exercised over his projects. After a difficult experience with studio interference on Spartacus, he refused to work without full creative authority. From that point forward, he was often involved in every major aspect of production. He wrote or co-wrote scripts, oversaw editing and cinematography, made casting decisions, and collaborated closely with designers and composers. The result is a body of work that feels not just directed, but authored in the fullest sense.

Kubrick’s early films, including Fear and Desire and Killer’s Kiss, hinted at his fascination with structure and ambiguity. The Killing, his 1956 breakthrough, introduced a fractured timeline and tightly controlled aesthetic that immediately set him apart. With Paths of Glory, he moved into political and ethical terrain, exploring the machinery of war and injustice with stark moral clarity. These early films earned him critical attention and paved the way for larger projects.

Although Spartacus brought commercial success, it lacked the creative freedom Kubrick demanded. He reclaimed that freedom with Lolita, a dark and subversive adaptation of Nabokov’s novel. He followed with Dr. Strangelove, a Cold War satire that turned nuclear anxiety into a surreal and unforgettable comedy. Peter Sellers’ multiple roles and the film’s bold tone revealed Kubrick’s capacity to merge performance, politics, and style in a way few directors had done before.

In 1968, Kubrick released 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film that marked a turning point in cinematic history. Co-written with Arthur C. Clarke, the film fused speculative science fiction with abstract philosophical inquiry. Its iconic visuals, use of classical music, and minimal dialogue broke from narrative convention and opened the door for a new kind of cinematic experience. Kubrick followed this with A Clockwork Orange, which sparked global controversy for its stylized violence and bleak social critique. It was a film that resisted moral certainty, challenging viewers to confront uncomfortable questions about free will and control.

In the 1970s and 80s, Kubrick continued to defy expectations. Barry Lyndon used natural lighting, period-accurate lenses, and painterly compositions to immerse viewers in 18th-century Europe. While initially misunderstood, the film is now widely praised for its visual innovation. The Shining reimagined horror as a psychological and spatial experience. With its use of long tracking shots, stark interiors, and disorienting atmosphere, it remains a defining film in the genre. Kubrick took a similarly unique approach to war with Full Metal Jacket, blending a brutal boot camp sequence with the surreal chaos of combat in Vietnam.

His final film, Eyes Wide Shut, explored eroticism, secrecy, and psychological unease in a slow, dreamlike rhythm. Though polarizing upon release, the film has since been reevaluated for its formal ambition and thematic consistency. It is a fitting final work from a director who never stopped pushing the boundaries of cinematic expression.

Kubrick’s influence on global cinema is profound. He transformed technical practices, pioneering methods like front projection in 2001, natural lighting in Barry Lyndon, and fluid camera movement in The Shining. He redefined genre expectations, elevating science fiction into philosophical exploration and horror into psychological disintegration. His thematic interests—human violence, institutional failure, the tension between reason and instinct—resonate across cultures and continue to inspire directors today, including Christopher Nolan, Claire Denis, and Paul Thomas Anderson.

Perhaps most importantly, Kubrick proved that film could be art without explanation. His work resists easy interpretation and often avoids emotional closure. He trusted the viewer to think, to reflect, and sometimes to be disturbed. That trust, along with his total creative control and technical innovation, makes him not only a great director, but a lasting example of what it means to be an auteur.

Perhaps my favorite documentary about Stanley Kubrick, of which there are many, is Stanley Kubrick A Life in Pictures (2001).

Stanley Kubrick A Life in Pictures (2001)

Materials included within this Project:

Custom Page:

Stanley Kubrick and His Endings

Interview:

Stanley Kubrick 1965 Interview with Jeremy Bernstein

Critical Review:

Film Review by Pauline Kale: Stanley Strangelove (1972)

Films:

Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

Documentary: